Climate tech defies economic gloom to pull in VC funding

Climate tech is bucking the downward trend for investment, with observers predicting major growth opportunities. Others warn more government clarity and commitment is needed.

Amid inflation, rising energy prices and interest rates, climate tech is one sector still capable of attracting venture capital. Five climate tech startups drew in a combined $3.7bn in the third quarter of 2022, outstripping investments in other sectors, according to CB Insights, while the VC market overall experienced its biggest quarterly drop in a decade.

Stefan Gross-Selbeck, managing partner at BCG Digital Ventures, part of the Boston Consulting Group, says despite the headwinds elsewhere, the sector represents a “tremendous” growth opportunity. “The peculiar situation we have is that if you believe in a net zero future, there are not a million ways to get to net zero – there are only a few. It’s difficult to imagine a net zero world without a massive hydrogen economy, renewable energy and corresponding infrastructure such as storage and smart grids,” he says.

Unlike ‘cleantech’, early stage companies focused on climate change mitigation, which boomed in the early 2000s before many companies went bust, climate tech refers to the decarbonisation of the economy in a range of sectors, mostly relating to energy but also in other climate- or nature-related sectors such as food and agriculture.

For Gross-Selbeck, who has spent some 15 years building digital businesses, this marks a departure with previous moments of tech disruption. “With [ride-hailing app] Uber, it was a market risk not a technology risk. With climate tech, there are massive technology risks in some areas. I’m not suggesting it’s easy but the opportunity areas are quite apparent,” he says.

According to BCG’s calculations, 25–30 per cent of net zero transformation can be achieved with existing technology; another 45–50 per cent will come from scaling technologies, such as hydrogen; and 20 per cent of technology that doesn’t yet exist.

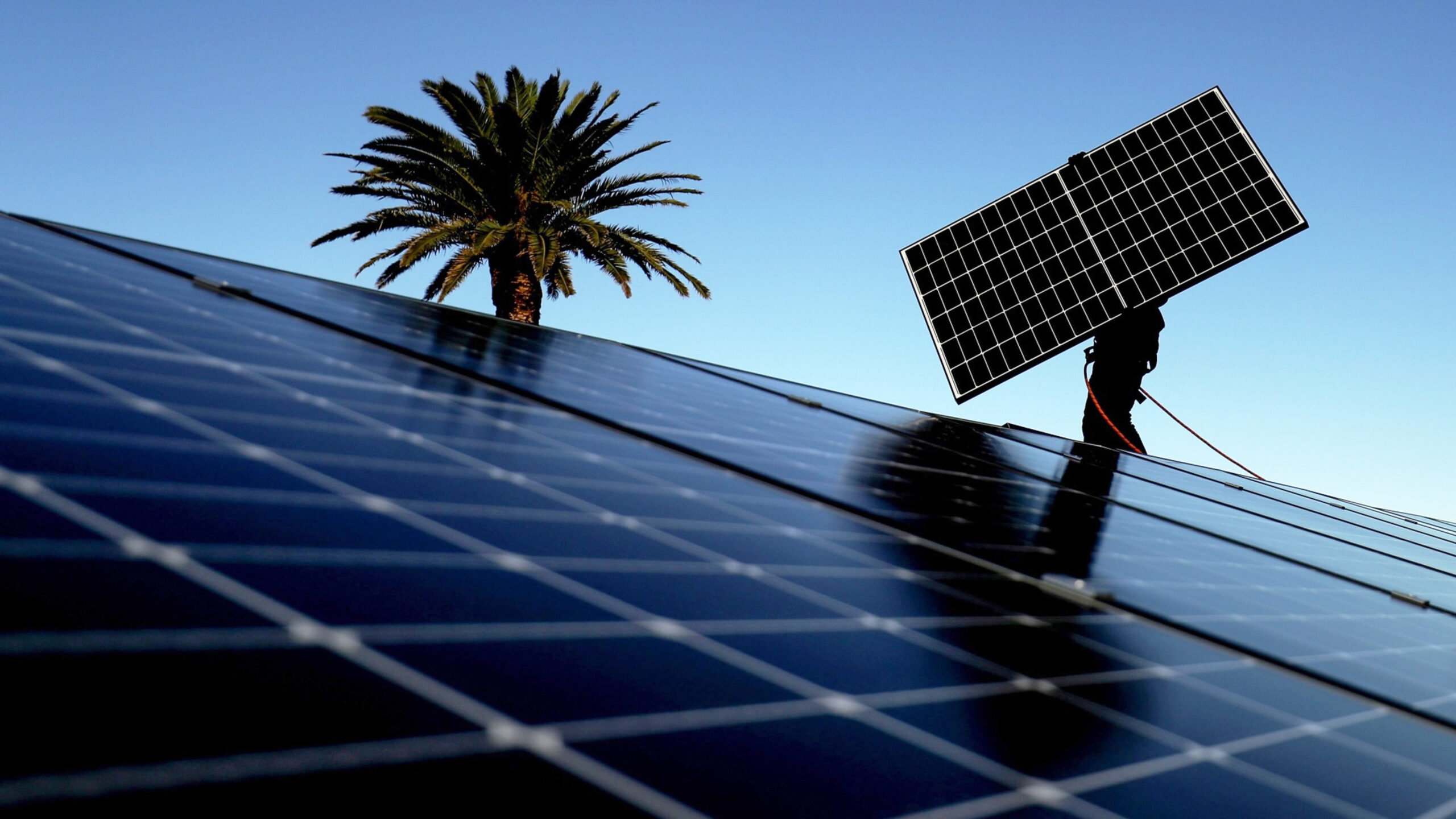

From green hydrogen and electric vehicles to rooftop solar panels, there is a will among both investors in and outside the VC community and policymakers to reshape the energy system. But despite the innovation that has taken place so far and the falling costs of wind and solar power, uncertainty persists on how much of this technology will be implemented and consolidated for the industries, businesses and households of the future.

Investment needed

In its World Energy Outlook 2022, the International Energy Agency warned that clean energy annual investments, which currently stand at $1.3tn, would only reach $2tn in 2030 following governments’ existing polices and measures under development – while over $4tn of annual investments is required by then to reach net zero in 2050.

Governments in advanced economies have issued incentive packages mobilising billions of dollars-worth of investments in their own territories, such as the US’s Inflation Reduction Act, the EU’s Fit for 55 package and REPowerEU, and Japan’s Green Transformation plan.

The Inflation Reduction Act, which allocates $369bn to incentive decarbonisation and clean energy, is a “massive game changer”, says Gross-Selbeck. “I think people are underestimating this: it will turn the US into the most attractive market for many of these technologies, including hydrogen.”

The IEA estimates countries that have adopted hydrogen strategies have committed at least $37bn, and the private sector has announced an additional investment of $300bn. Fortescue Future Industries, the green hydrogen arm of Fortescue Metals Group, for instance, has pledged billions to green hydrogen investments. Egypt, meanwhile, has attracted over $100bn of green hydrogen investment announcements (green hydrogen is hydrogen produced from renewable sources via electrolysis).

Jonas Moberg, CEO of Green Hydrogen Organisation, a non-profit advocating for the expansion of the green hydrogen economy, says modern society cannot be decarbonised without it. As the use case for green hydrogen is industrial, early takers for green hydrogen and green ammonia will be in fertilisers, green steel and bunker fuel, he adds.

Asked if the ‘hydrogen hype’ poses any risks to the ambition of the green hydrogen economy, Moberg is confident that the sector will develop, even if not all the announced investments turn into a reality. “But how fast it will happen will depend on getting the sequencing right,” he adds, referring to all the engineering, planning and permitting required and the development finance needed for the offtake investments.

Risk of backpedalling

SET Ventures partner Julia Padberg says while 2022 saw record amounts of investment into climate tech, “governments need to do more, not only in terms of spending but also in terms of reshaping existing markets by offering more incentives”. On top of this, she adds, governments have been weakening on their climate ambitions by reopening coal-fired power plants and reneging on green hydrogen legislation.

In September, the European Parliament voted through an amendment to the Renewable Energy Directive II, which scrapped an act that would have imposed requirements that all green hydrogen producers source electricity from dedicated renewable energy projects. Now these producers can procure green electricity from the grid provided that they obtain power purchase agreements from renewable energy installations for the equivalent amount. By 2030, the EU has targeted to produce 10mn tonnes of green hydrogen annually and to import an additional 10mn tonnes from outside the bloc.

Padberg believes this will lead to more dirty energy being used to produce hydrogen – ultimately adding to overall emissions rather than removing them. “Green hydrogen will become a textbook example of greenwashing,” she says.

Elsewhere, EV ambitions are being hit by a harsh economic reality. UK battery producer Britishvolt, which had plans to build a multibillion-pound gigafactory in the north of England, found itself on the brink of collapse, as of October 31. This is due to a cashflow problem and the fact that the company didn’t secure any orders from a car manufacturer. Even if capital raising is not an issue for the industry, the near-collapse, which has since been averted, shows that basic economics still applies.

Caspar Rawles, chief data officer at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, says the Britishvolt case highlights the challenges in setting up cell production from scratch. “The vast amounts of capital required, even in the early stages of project development make it tough for companies without large balance sheets, such as automakers, or incumbents, to make headway towards production,” he says.

While he doesn’t see this as a technology risk for the industry, Rawles stresses that “capacity plans do not equal production” and many of the planned cell plants either won’t make it to production or will experience delays.

Next steps

As the path towards a greener future is also set to become more digitised and decentralised, the use of software to manage energy supply will become increasingly important for business consumers and households. According to Philip Schröder, CEO of 1komma5, one of Germany’s foremost solar startups: “We see investors move away from partial tech players to solution providers like us.” 1komma5 (whose name alludes to the goal of 1.5C warming) is a one-stop shop selling solar panels, energy storage units, heat pumps, EV charging stations and software to help consumers manage their energy consumption on an individual basis.

While the energy markets are fragmented into various actors and players, from renewable energy companies supplying energy to the national grids to energy retailers and infrastructure providers, Schröder believes it will consolidate over the next decade. “Now there are tens of thousands of businesses in this sector. I would say that in 10 years there will be five or six players in each of these segments in Europe. Electricians, roofers and others will be replaced by bigger solution providers,” he says.

Another part of the decarbonisation puzzle is the use of “more niche” technologies among smaller companies in the circular economy, according to Martin Conroy, portfolio manager at KBI Global Investors. “While these may not have the same impact in terms of reduction of emissions, they’re easier to implement or improve the economics in a certain setting,” he says.

One such company is San Francisco-based Afresh, which uses artificial intelligence to optimise supply chains and operations for large grocers. With a total of $148mn capital raised, it has grown over tenfold in the past year and expects to be used by over 2,500 US stores by the end of year.

“Innovations in food and agriculture are non-negotiable if we want to prevent a climate crisis, yet companies addressing inefficiencies in our food system are often overlooked in the climate tech conversation,” says Afresh CEO Matt Schwartz.

Gross-Selbeck at BCG Digital Ventures concedes that investors in the climate tech sector are all contending with the same macroeconomic issues of rising inflation, energy prices and interest rates – all of which are “going in the wrong direction”. But he adds: “Having said that, everyone continues to believe that the climate transition is going to happen. With everything happening with energy prices in Europe, we have to.”

Similar Articles

In Charts: Canada, Japan, South Korea ‘blocking clean energy transition’ with fossil fuel finance