Hopes that World Bank head will focus on climate change

Many have high hopes for presumptive World Bank head Ajay Banga, though others wished for the leadership of a woman.

Despite many hoping for a female nominee from a global south country, Ajay Banga – the former chief executive of Mastercard – has been named by US president Joe Biden as the replacement for David Malpass as president of the World Bank.

However, Banga is considered by many to have the qualities needed to reform the institution and put climate change closer to the heart of the bank’s work.

Malpass’s position at the World Bank was thrust into doubt last September when he seemed to suggest he was a climate change denier. “I’m not a scientist,” he replied, when asked whether he believed in anthropocentric global warming.

He subsequently rolled back his comment during an interview with CNN, insisting: “It’s clear greenhouse gas emissions are coming from man-made sources, including fossil fuels, methane, the agricultural uses, the industrial uses — so we’re working hard to change that.”

But few would agree that Malpass “worked hard” to instigate policies to bring down emissions during his tenure. “From a climate perspective, the bank did not use its leadership position to push the boat out on delivering climate finance and different parts of the climate transition,” says Sonia Dunlop, programme leader of public banks at climate think-tank E3G.

Addressing climate change

The bank says it delivered a record $31.7bn in 2022 to help countries address climate change, a 19 per cent increase on the previous year. Yet this sum is well below par, say climate campaigners, given the $125tn of climate investment needed by 2050, if the world is to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to well below 2C, according to research from the UN high-level climate action champions.

Climate finance from the World Bank could increase by more than $13bn a year by 2025 if the bank’s climate target was raised to 50 per cent of its overall finance, according to research by US non-governmental organisation NRDC. The bank says that 36 per cent of its financing in 2022 supported climate action.

Further, last year the bank provided at least $930m in finance for fossil fuels, largely for gas, says NGO Oil Change International.

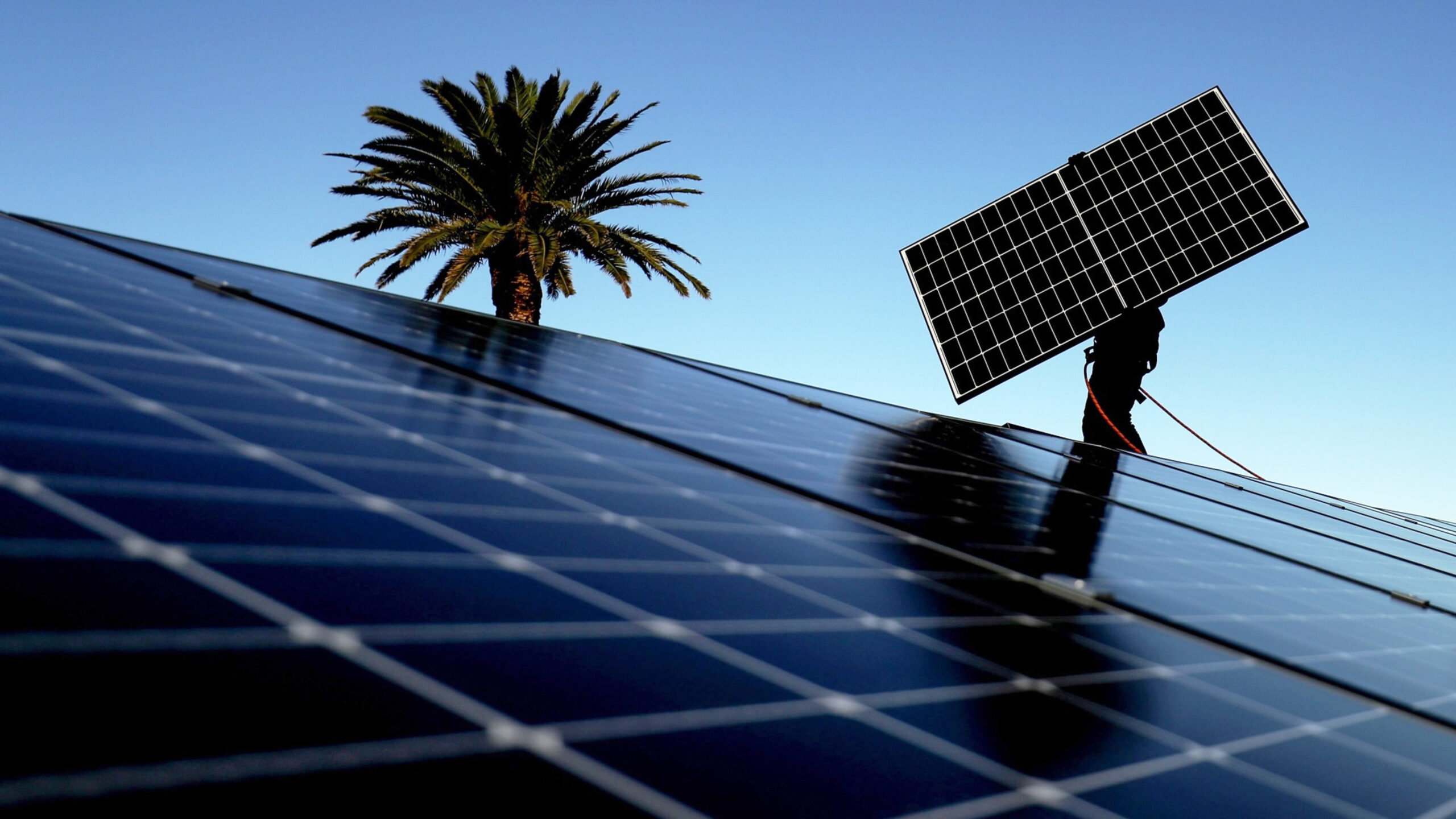

Switching this financing to renewables would make a huge difference, suggests a recent International Energy Agency report. It shows that achieving energy access across Africa by 2030 will require clean energy investments to more than double to $25bn annually, the same cost as building one new liquified natural gas terminal a year.

Pressure for the World Bank to raise its climate game has not just come from environmental NGOs, but also influential names in the finance world, such as US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen. At an event in February, Yellen urged the bank to “evolve” and be “bolder and more imaginative” in its approach to tackling global challenges such as climate change.

Many felt it was time for the US, which traditionally appoints the head of the bank, to put forward a woman for the post. “It is definitely time for a woman to lead the World Bank,” tweeted Svenja Schulze, World Bank governor and German minister for economic co-operation and development, in February.

The US could, in theory, still name other candidates to replace Malpass, but the most likely scenario is that Ajay Banga will take up the post on May 1.

Not a woman, but…

“We were expecting a woman, that was the least of our expectations,” says Turkey-based Cansin Leylim, associate director of global campaigns at climate campaign group 350.org. “We were keen to see a woman from a global south country or from an indigenous community. In 2023, that shouldn’t be such a wild ask.”

But it is still a step forward. “[He] is not a woman, but he is from a developing country and he is Sikh,” points out Dunlop.

Banga is a US citizen, but was born, grew up and was educated in India. “This is a historic choice, and we should mark that,” she says, adding that a female candidate can wait until next time.

Rachel Kyte, dean of the Fletcher School at Tufts University, rues the general lack of women in the “international system”, but says she is “excited” by Banga’s nomination. The bank needs “a quality CEO, a change-management leader, and someone who gets the climate emergency”, she says.

Kyte believes Banga can deliver on governance and climate. “He gets the complexity of the transition,” she adds, citing his track record at Mastercard, where he “bet big on financial inclusion”.

At the financial services company, Banga was “a leader in setting targets for net zero and the first such institution to gain approval from the Science-Based Targets initiative”, said Lord Stern from the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, and formerly of the World Bank, in a statement. “He is also on the advisory board of Beyond Net Zero, a climate finance fund.”

In January 2020, Banga wrote a blog insisting that “the time for environmental altruism is over”, and it was time “for everyone – companies, consumers, communities – to find paths for collective action on climate change”. The piece suggested “he gets the challenge and the fact we are in an emergency”, says Dunlop.

Banga’s appointment to the World Bank looks secure, given that it has also received cross-party support in the US, though certain Republican politicians take a different view of on the climate.

House Financial Services Committee chair Republican Patrick McHenry accused the Biden administration, in a statement, of “time and again […] putting its radical climate and social agendas ahead of economic prosperity”.

Focus on ‘alleviating global poverty’

The next World Bank president must “focus on the bank’s core mission of alleviating global poverty and the necessary reforms to confront China’s economic aggression, rather than progressive pet projects”, he added. “I am confident in Banga’s ability to fulfil this role.”

Climate change, for most of the world, is not a “progressive pet project” and Barbadian prime minister Mia Mottley’s Bridgetown Initiative makes clear that development and climate action go hand in hand.

Implementing at least elements of this plan should be part of Banga’s reform plan, says Kyte, as should the recommendations of the G20 report on multilateral development banks published last year. It suggested all MDBs could do more on reversing climate change, and with “very manageable changes to risk tolerance” they could boost their lending capacity by “several hundreds of billions of dollars over the medium term” while still maintaining their credit ratings.

It would be “really smart” to implement the G20 recommendations “and then go to shareholders for a big capital increase”, says Dunlop.

During Malpass’s tenure, the World Bank produced an “evolution roadmap” exploring what more it could do to tackle climate change and other global problems. The bank concluded that to manage development and climate goals, it would need an injection of cash from shareholders.

The evolution roadmap was widely criticised. “It is woefully inadequate and needs revamping or starting again,” says Kyte.

For Leylim, Banga’s first decision should be to stop all fossil fuel funding and engage with the issue of debt to give lower-income countries more fiscal space for the energy transition. In theory, from July 1, all World Bank projects should be aligned with the Paris Agreement, but applying this pledge is “complicated”, says Dunlop, describing the bank’s checks and balances as “weak and secretive”.

Addressing the bank’s governance would also help climate action, says Kyte, adding that climate projects are approved but the finance is dispersed too slowly.

“There is some brilliant climate analysis” by the bank, “but this is not what it is lending against”, she says. Banga needs to “clean the house” – if people are not onboard for the reform agenda, “let them go”, she adds.

This article first appeared in The Banker.

Similar Articles

In Charts: Redemptions drag global climate fund flows to lowest level in four years

In Charts: Canada, Japan, South Korea ‘blocking clean energy transition’ with fossil fuel finance