With many investors still underweight on the Asian superpower, policy tailwinds are opening up large avenues for sustainable capital. However, experts warn that getting the analysis right is crucial

As skiers and snowboarders soared against the backdrop of a disused steel mill at Beijing’s winter olympics this week, China’s commitment to sustainability was thrust into western public consciousness.

While users flocked to social media to comment on the dystopian aesthetics of giant smokestacks, the Shougang site’s re-use is actually part of a regeneration project in the west of the city, turning an industrial site into a cultural venue powered by renewable energy.

International investors have taken a similarly cautious view – despite accelerating inflows into the country, China’s inclusion in the MSCI All World Index stands at 3.7 per cent for a country that accounts for close to 20 per cent of global GDP. Global equity managers are 4.5 per cent underweight on Chinese stocks according to Emerging Portfolio Fund Research, MSCI and Goldman Sachs research, and asset owners are anecdotally similarly positioned. But can sustainability-minded investors afford to ignore the world’s second largest economy and largest source of emissions?

Use-of-proceeds boosts investor confidence

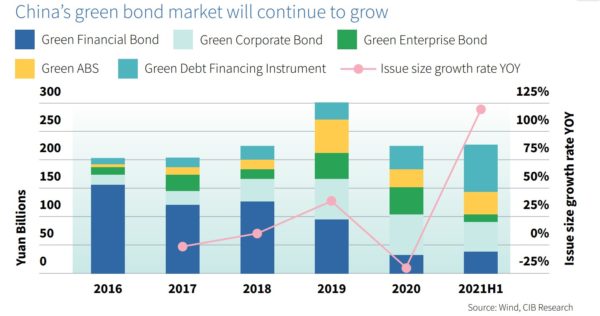

Rapid growth in the Chinese green, social and sustainable (GSS) debt market has meant there are now a wealth of outlets for sustainability-conscious investors to deploy capital in the country.

With structural incentives in place such as risk-weighted adjustments to bank capital requirements when using green assets as collateral, the total issuance of labelled debt reached RMB3.3tn ($520bn) at the end of the first half of 2021, according to Chinese financial research company Wind and the Climate Bonds Initiative.

Green, blue and carbon-neutral bonds issued in China now account for $220.2bn of a $1.3tn global cumulative issuance, according to a recent CBI report. Where issuance had previously largely been concentrated among banks, the share of financial green bonds is steadily dropping as corporate bond issuance picks up.

Sean Kidney, chief executive of the CBI, says this shows the seriousness of the Chinese decarbonisation project, which he says “is not driven by investors; it’s driven by government incentives”.

China’s commitments at the COP26 conference in Glasgow to reach carbon peaking by 2030 and achieve neutrality by 2060 drew criticism for lagging western countries, as Beijing has played a large role in sending power generation from coal to record levels.

A commitment to common prosperity means the Chinese government is unlikely to take measures that significantly hurt holders of outstanding debt linked to coal, says Kidney, but he does say that coal companies have struggled to attract new capital due to caps on the level of bank loans to the sector, and points to backlash against recent coal finance as a sign of the times.

After economic stimulus during the Covid-19 pandemic led to local governments building coal-fired power stations approved by the National Energy Administration, in January 2021 a scathing central government criticism said the NEA had failed to follow Xi Jinping’s ‘Thought of Ecological Civilisation’, according to Reuters.

“In China, you don’t get much more serious a condemnation than that,” says Kidney.

He points to measures western politicians have not yet been able to stomach, such as the People’s Bank of China’s risk-weighted capital requirements, or the exclusion of gas and nuclear from its taxonomy, adding: “That’s an indicator of the extent to which China is taking this seriously.”

Reforms are still needed in the bond market, however. Though largely ironed out, inconsistencies between the Chinese green bond framework and the EU’s green taxonomy, such as the inclusion of small amounts of supercritical coal financing in Chinese bank bonds, have meant large chunks of debt cannot be included in the EU-China common ground taxonomy that the two jurisdictions are working on, creating compliance headaches for sustainable western investors.

A further issue, says Kidney, has been Chinese companies’ circumvention of local limits on use of proceeds for refinancing by allocating these instead to ‘working capital’ – this lack of transparency has made bonds financing otherwise strong sustainable projects difficult to align with international frameworks.

But there are avenues for the green bond to grow even further, offsetting these framework mismatches. Kidney says the CBI has a working group looking to encourage the inclusion of sustainable property in green bonds (the PBoC is understood to be reticent about aiding China’s scandal-ridden property sector), while he encourages energy majors like Sinopec to look at financing its large green hydrogen plants via use-of-proceeds debt.

Tailwinds in equities

If a level of international commonality around use of proceeds could be comforting international investors, equity markets do not quite feature the same guarantees.

Evidence suggests Chinese companies’ disclosure and engagement with investors, though vastly improved, still leaves something to be desired.

But investors are turning cautiously optimistic, with the FT reporting in November that a number of banks have now begun advising clients to remedy underweight positions.

Those underweight positions had been cemented by a difficult 2021 for Chinese stocks, where waves of new regulation under the banner of the ‘common prosperity’ policy hit share prices in several sectors.

But for equity investors interested in pursuing environmental, social and governance themes, it seems unlikely that regulation will hurt them as badly as, say, tech investors reliant on the share price of Tencent and Alibaba.

“If you look at the longer-term policy tailwinds, which will include electric vehicle car makers, solar and renewables, those are areas we focus on ourselves because we know that government policy tailwinds will aid those sectors,” says Ken Wong, Asia equity portfolio specialist at Eastspring Investments.

Disclosure stakes are high

Wong says interest from clients in China, particularly from Europe, is picking up, while at the same time disclosure is improving.

He estimates that the vast majority of Chinese companies now disclose some ESG metrics, with around one in five now verified by independent analytics vendors.

The country still lags other emerging markets on disclosure scores, and “this is where China definitely does need to step up its game”, Wong stresses, but he points out a much improved willingness of corporates to communicate with investors: “More and more are hiring investor relations teams to deal with it. The fact is that it was much more difficult to get a specific answer from the [financial director] or CFO previously.”

Poring over the details of disclosures is of paramount importance for all investors in China, says Faisal Rafi, head of research at RisCura, an investment consultancy specialising in emerging markets such as China and southern Africa, given the government’s immense ‘carrot and stick’ power.

“It’s very important to do the work and make sure one is investing in sustainable assets, because when the government gets wind of malpractice, unlike the UK where change can take a long time, the Chinese government can change things overnight,” he says. “The stakes are very high for getting it wrong.”

Pension fund investors can sometimes be reluctant to allocate to China, citing social concerns, he says, but stresses that it is important to disaggregate Chinese companies from the state.

“There are lots of global companies who are backing China in ways that we wouldn’t agree with… whereas there may be some great companies in China,” says Rafi, arguing that Chinese dominance in manufacturing means investment in this region can be the only way of accessing some key environmental themes.

“The reality is that, so far as ESG funds are concerned, if they’re to invest in companies that operate in this area, then they might find that a big percentage of this universe lies in China,” he adds.

There may always be some investors who cannot stomach allocations to a country associated with human rights transgressions, or indeed a huge source of emissions, like China.

But in the context of climate change, which Kidney characterises as an “extinction threat”, failure to engage with a country for ethical reasons could be equally unpalatable. He adds: “I’d happily work with North Korea if it might lead to the greening of their economy.”

Similar Articles

Trade union leaders call for energy transition jobs ‘in same region’ as fossil fuel jobs

In Brief: EU parliament rubber-stamps CSDDD; US imposes strict rules on carbon pollution from power plants