Why it is time to add the ‘D’ of democracy to ESG standards

High democratic standards are good for both people and investors – something markets appear to overlook

On April 6, 2023, little more than a month before Turkey’s May 14 presidential election, and less than five months after main opposition politician Ekrem Imamoğlu was sentenced to two years in prison, the Turkish government issued its first ever green bond.

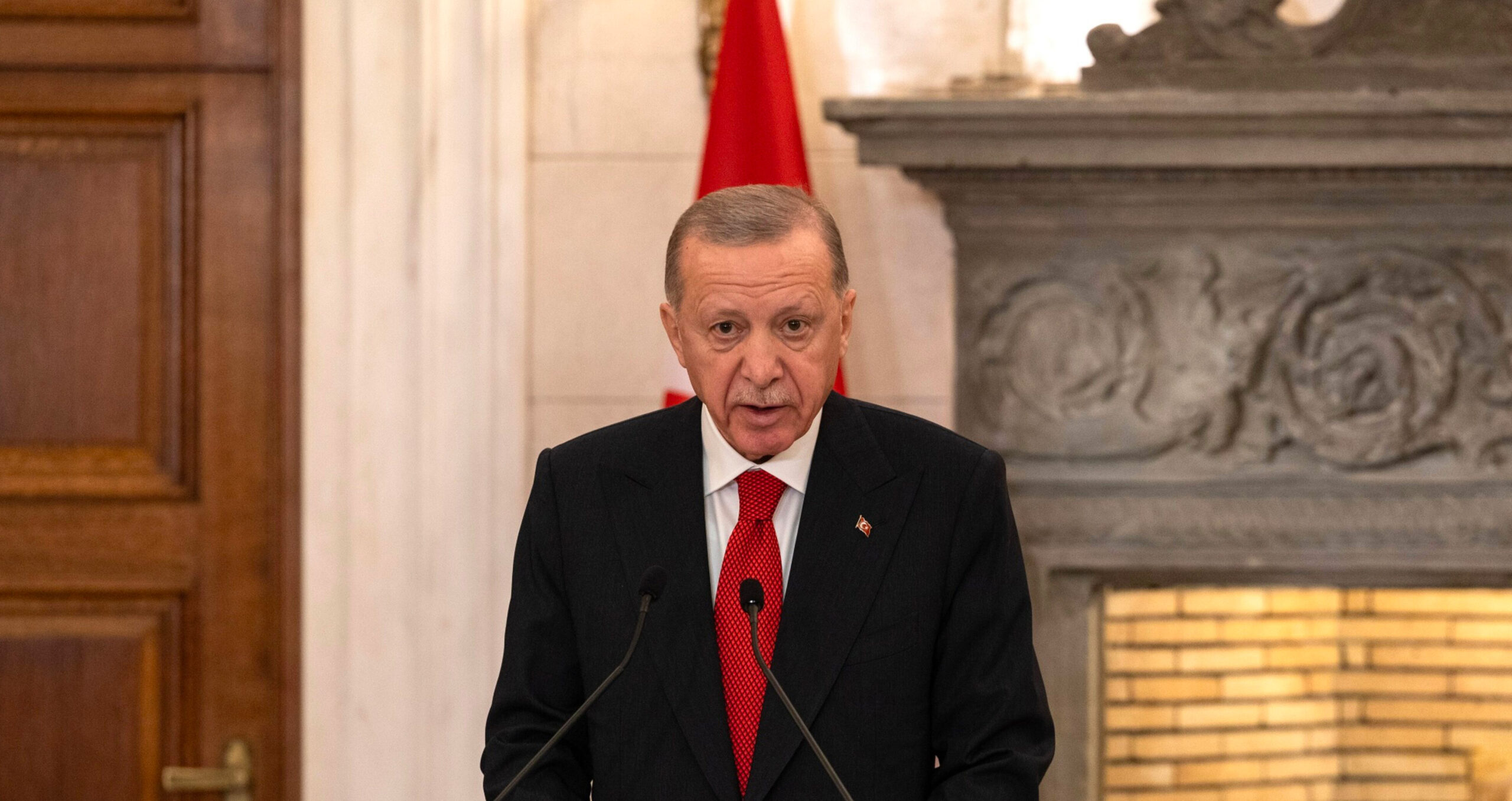

The administration of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who was vying for his second presidential re-election, raised $2.5bn, in a deal that was three times oversubscribed. The deal helped to put Turkey on the ESG map. By the time Turkey’s green bond was issued, most polls indicated that Erdoğan would lose against Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu, the candidate who was able to unite most of the opposition.

Erdoğan’s popularity had suffered as inflation soared, reaching 86 per cent in 2022; however, by April 2023 his government was spending like there was no tomorrow. Weeks before the election, he raised public sector wages, announced free natural gas for households for one year and inaugurated several megaprojects, among other populist measures. Defying the polls, Erdoğan got 49.5 per cent of the votes in the first round, winning re-election in the May 28 run-off.

First elected prime minister in 2003 before becoming president in 2014, Erdoğan will be president until 2028. Under his tenure, Turkey has lost all semblance of a liberal democracy. Acclaimed Turkish novelist and essayist Kaya Genc has called her country “the world’s largest prison for journalists”. But the markets are oblivious to this obliteration of democracy.

The markets celebrated the Turkish government’s issuance of a green bond, forgetting that money is fungible. Budgetary frameworks aimed at ensuring proceeds from green, social and sustainability bonds are allocated to their stated purposes are weak, including in the EU. Even if the money were allocated to green projects, it could free up budget resources that autocrats and wannabe autocrats could allocate to repressive policies instead.

Autocratic issuers

Turkey is not the only autocracy issuing GSS bonds. By my measure, of the 35 countries that issued GSS bonds by 2021, around 11 were autocratic.

After his re-election, Erdoğan reinstated orthodox monetary and fiscal policies, and the markets loved it: government bond issuance and its local stock market prices soared. According to an article in the Financial Times in February, Turkey’s stock market gains in 2024 are the highest among all MSCI All-World indices. Investors poured $233mn into major Turkish tech-focused funds last year.

These investors seemed to have forgotten that exactly one year before, most pundits had declared the Turkish stock market uninvestable. A Bloomberg article in February 2023, headlined “Turkey’s state-backed markets have few charms for foreigners”, argued that foreign investors did not want to put their money in a market in which rules change at the whim of the powerful.

However, after the elections, orthodox fiscal and monetary policies were established and in investors’ minds, market stability triumphed over democracy and the respect for human rights. Such a view is, though, short-sighted. Higher democratic standards protect not only the rights of citizens, but also property rights and the rules of the game for investors. Downside financial risks are higher when the division of power, a free press, an independent judiciary, and strong non-governmental organisations do not prevail.

Take the case of Russia. By the time it invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Russia’s government bonds had a bigger share in JP Morgan’s ESG version of the EMBI Global Diversified – the most tracked emerging markets sovereign hard currency bonds index – than in the non-ESG-corrected one.

This incongruity arose because the ESG-corrected version of the EMBI Diversified used ESG scores provided by Sustainalytics and RepRisk, which do not take democracy into consideration. On the day of the invasion, Russia’s RTS index dropped 38 per cent, while government bonds dropped 45 per cent.

These stories underline the need to add consideration of democracy to ESG. In the same way that markets respond to investor concerns about climate change and the environment through ESG integration, it is time they also responded to another threat the world is facing: democratic recession.

While measuring democracy might be harder than measuring the carbon impact of a project, the correlation among the main democracy indices is remarkably high, and they can provide institutional and individual investors with the tools to start adding a D of democracy to ESG.

In this way, they will not only be doing good but they are also more likely than not to end up doing better.

Marcos Buscaglia is author of “Beyond the ESG portfolio. How Wall Street can help democracies survive” (McGraw Hill)

Similar Articles

Editor’s note: solidarity in clean tech production

Editor’s note: a kaleidoscope of perspectives